IMO Problem Explorer

Explore what makes the International Mathematical Olympiad the hardest math exam in the world. This tool provides sample problems from different competition areas to experience the kind of creative problem-solving required at the highest level.

Enter the problem area and click "Show Sample Problem" to see a real-world challenge similar to those in the International Mathematical Olympiad.

The hardest math exam in the world isn’t held in a university lecture hall or a corporate testing center. It’s a three-day, six-problem challenge taken by the top 600 high school math students on the planet. This isn’t a test of memorization or speed. It’s a battle of creativity, logic, and raw problem-solving power. The International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) is the undisputed peak of secondary school mathematics-and it’s not even close.

What Makes the IMO So Hard?

Most people think of math exams as equations, formulas, and multiple-choice questions. The IMO doesn’t just ignore that model-it flips it upside down. Each problem is designed to be unsolvable by brute force. You won’t find anything from your textbook. Instead, you’re handed a puzzle that looks like a riddle written by a genius who hates easy answers.

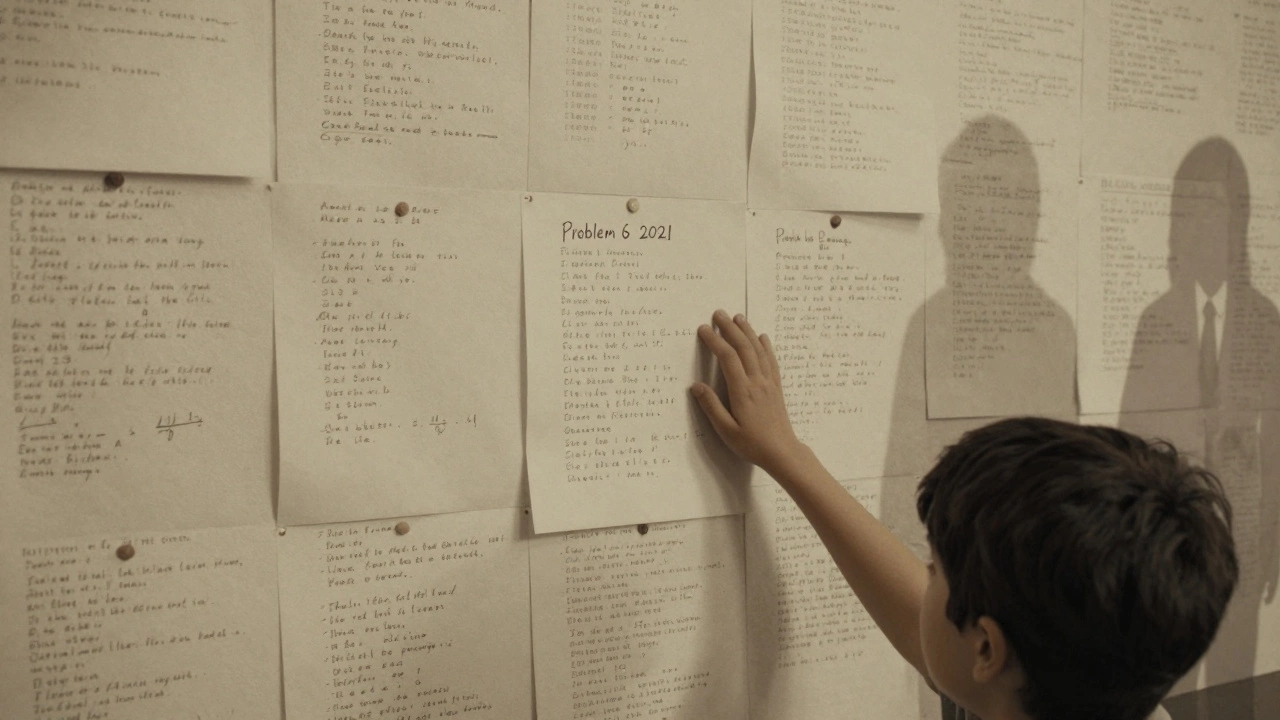

Take Problem 6 from the 2021 IMO: Prove that for any integer n ≥ 100, there exists a set of n positive integers such that the sum of any subset of them is not divisible by n.

That’s not a calculation. That’s a proof. You need to construct a pattern, justify why it works, and rule out every possible counterexample-all in under 90 minutes. And you have to do that twice a day, for three days. No calculators. No notes. Just pencil, paper, and your brain.

The problems come from five areas: algebra, geometry, number theory, combinatorics, and occasionally, functional equations. These aren’t advanced college topics-they’re deep, elegant twists on ideas taught in high school. But the depth? That’s where the difficulty explodes. A geometry problem might require you to invent a new construction. A number theory question could demand you combine modular arithmetic, prime factorization, and induction in a way no one has ever seen before.

Who Takes the IMO?

Every country sends a team of six students, selected through brutal national competitions. In China, students spend years training in specialized math schools. In Russia, the top performers are pulled from regional math circles that meet weekly for years. In the United States, students climb a ladder: AMC → AIME → USAMO → IMO Training Camp. Only about 500 students out of 500,000 who take the AMC 12 make it to the USAMO. Of those, maybe 12 get invited to the camp. Six get chosen.

The average score on the IMO? Around 15 out of 42. A perfect score-42 points-is rarer than a Nobel Prize in math. Only 14 people in history have ever achieved it. The top scorers don’t just win medals-they become legends. Terence Tao, who won a gold medal at age 13, went on to win the Fields Medal, math’s highest honor. Maryam Mirzakhani, the first woman to win the Fields Medal, was an IMO gold medalist in 1994.

Why Doesn’t Anyone Else Come Close?

Other tough exams exist. The Putnam Competition for undergraduates is brutal, but it’s open to college students. The Cambridge Mathematical Tripos is legendary for its length and rigor, but it’s still a curriculum-based test. The IIT JEE Advanced in India is known for its intensity, but even its hardest problems are solvable with standard techniques if you’ve practiced enough.

The IMO is different because it’s not about preparation-it’s about insight. You can’t drill your way to solving an IMO problem. You can’t memorize a formula that will help. You need to see connections no one else sees. It’s like chess, but instead of learning openings and endgames, you’re inventing new rules every time you sit down.

One former IMO participant described it this way: “It’s not about being smart. It’s about being stubborn. You stare at a problem for three hours. You try 20 different ideas. You write down 50 pages of failed attempts. And then, suddenly, you see it-not because you learned it, but because you refused to give up.”

How Do Countries Train for It?

Training for the IMO isn’t like studying for a SAT or AP exam. There’s no textbook. No Khan Academy playlist. No practice tests with answer keys.

Teams train using problem archives-thousands of past IMO problems, regional olympiad questions, and problems from journals like The American Mathematical Monthly. Students spend months working through these, not to memorize solutions, but to build intuition. They learn to recognize patterns: when a problem feels like it needs induction, when symmetry suggests a geometric trick, when modular arithmetic is hiding in plain sight.

Coaches don’t teach solutions. They ask questions: What if you tried this? What happens if you assume the opposite? Can you restate this in another language? The goal isn’t to find the answer-it’s to learn how to think when you have no idea what to do.

China, Russia, South Korea, the United States, and Iran consistently dominate the medal count. But in recent years, countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Romania have risen sharply. Why? Because they’ve built systems. Small math clubs. Weekend camps. Mentorship from past winners. They don’t have more talent-they have better culture around problem-solving.

What Happens After the IMO?

Winning a medal at the IMO doesn’t guarantee a math career. But it does open doors. Top scorers often get full scholarships to MIT, Princeton, Stanford, or Cambridge. Many go on to become researchers, professors, or work in cryptography, AI, or quantitative finance.

But even those who don’t become mathematicians say the IMO changed how they think. Engineers say it taught them to break down impossible problems. Entrepreneurs say it gave them the patience to test 50 ideas before finding one that works. Programmers say it made them better at debugging-because they learned to trace logic backward when nothing makes sense.

One Google engineer, who won IMO gold in 2012, said: “I use the same mindset every day. When a system crashes, I don’t look for the error. I look for the pattern behind the error. That’s the IMO way.”

Can You Prepare for It?

If you’re not already among the top 0.1% of math students, the IMO is probably out of reach. But you can still learn from it.

Start with past problems. The official IMO website archives every problem since 1959. Try one a week. Don’t look at the solution until you’ve spent at least two hours on it. If you’re stuck, walk away. Come back the next day. Keep going. The goal isn’t to solve it-it’s to get comfortable with being stuck.

Read books like The Art and Craft of Problem Solving by Paul Zeitz or Problem-Solving Strategies by Arthur Engel. These aren’t textbooks-they’re collections of mindset tools.

Join a math circle or online forum like Art of Problem Solving. Talk to others who are stuck too. You’ll learn more from watching someone else struggle than from reading a perfect solution.

The hardest math exam in the world isn’t about being the smartest. It’s about being the most persistent. It’s about loving the process of not knowing-and refusing to quit until you do.

Why the IMO Still Matters

In a world obsessed with standardized testing and AI-generated answers, the IMO is a rebellion. It’s a reminder that human creativity still has a place in math. No algorithm can solve an IMO problem unless it’s been trained on millions of similar problems-and even then, it fails on the truly original ones.

The problems are designed to be impossible for machines. That’s why they’re still human. That’s why they’re still hard. And that’s why, after 65 years, the IMO remains the ultimate test of what the human mind can do when it’s pushed to its limit.